Last Updated on May 23, 2025

Does your child seem to learn slower than others their age?

Do they have trouble understanding instructions, solving simple problems, or remembering what they’re taught?

You might be wondering:

“Does my child have an intellectual disability?”

Intellectual disability in kids means a child’s thinking and everyday learning skills develop more slowly than expected. It’s not about being lazy or misbehaving. These children often try hard, but still fall behind in school, speech, or even simple daily tasks.

According to recent studies, 1–3% of children globally may have some form of intellectual developmental disorder.

Some kids show signs as toddlers. Others struggle quietly in preschool or early primary school before anyone realises they need help.

This article will help you:

- Understand what intellectual disability really is

- Spot early signs in toddlers, preschoolers, and school-age kids

- Learn what causes it and how it’s diagnosed

- And most importantly, find ways to help your child grow, learn, and feel understood

What Is Intellectual Disability in Children?

Intellectual disability means a child has trouble with thinking, learning, and doing everyday things compared to other kids their age. It isn’t just about school or academics it also affects how they talk, understand, remember, and take care of themselves.

Children with an intellectual disability may:

- Learn new things more slowly

- Struggle with communication or following instructions

- Need more help than others with daily tasks like getting dressed or brushing teeth

- Have difficulty making friends or understanding social rules

This condition is sometimes called intellectual developmental disorder, especially in medical settings. It usually starts before age 18 and can range from mild to profound.

Some children with intellectual disabilities also have other conditions like autism, ADHD, or learning disorders which can make diagnosis and support more complex, but also more important.

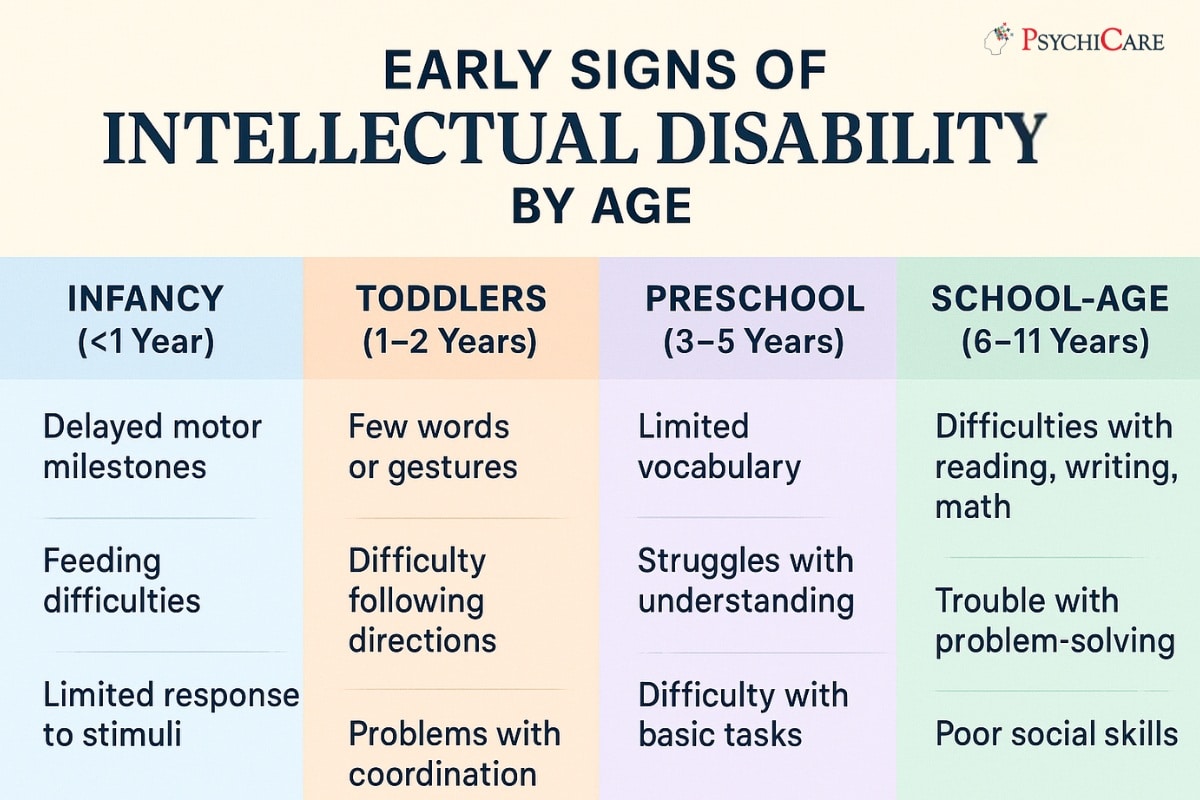

Early Signs of Intellectual Disability by Age (What Parents Actually Notice)

Intellectual disability doesn’t always show up in a dramatic way. Often, it’s a slow, quiet difference one that parents notice before anyone else does.

You might not hear “something’s wrong.” You just feel something’s… different.

Here’s what that difference can look like as your child grows:

Babies (0–1 year old)

You keep waiting for milestones… but they don’t come.

- Other babies are sitting, babbling, crawling, yours just watches.

- You clap and smile, but they don’t copy you.

- They rarely look at faces, or they stare right through you.

- You pick them up, and they don’t reach back.

You might hear, “Every baby’s different.” But your gut tells you to keep watching.

Toddlers (1–3 years old)

Other kids are running around. Yours still needs help with everything.

- They say one or two words and then stop.

- They don’t point to things or wave bye.

- If you say, “Give me the ball,” they look at you like you’re speaking a different language.

- They don’t pretend. No feeding dolls, no talking to toys.

- You’re still helping them eat, drink, or climb stairs while others are doing it all alone.

And when you ask the doctor, they say, “Let’s wait six more months.”

Preschoolers (3–5 years old)

You watch them try, but they get left behind.

- They don’t remember letters or colors, even after lots of practice.

- They forget how to count past three.

- They can’t explain what they want without pointing or repeating one word.

- Teachers say “He’s sweet, but he gets lost in class.”

- Other kids stop inviting them to play because they don’t know how to join in.

- You have to remind them to pull up their pants or use the toilet every single time.

You start to wonder: “Why is everything so hard for them, and so easy for other kids?”

School-Age Children (6+ years)

Homework turns into tears. Not just theirs, yours too.

- They struggle with basics like days of the week or tying shoelaces.

- They need constant reminders every morning, every night.

- They can’t explain what they learned in school, even right after class.

- Their friends are talking about video games and birthdays, and your child still can’t follow a conversation.

- They say things like “I’m stupid,” “I don’t get it,” or “Everyone is better than me.

Mild to Severe Intellectual Disability: What It Looks Like

Not all children with intellectual disability are the same. Some need a little extra help in school. Others may need full-time care throughout their lives.

Here’s what the different levels of intellectual disability often look like, not in medical terms, but in real day-to-day life.

Mild Intellectual Disability

Most kids with this level go to regular schools, but they often feel “behind.”

- They can talk, dress themselves, and play but schoolwork is a struggle.

- They have trouble understanding abstract ideas like time or money.

- It takes longer to learn things but with repetition, they get there.

- They may get picked on or left out because they seem “younger” than others.

- Many parents say, “He’s smart in his own way, but he learns differently.”

Moderate Intellectual Disability

These kids often need special education and day-to-day support.

- They speak in short sentences or simple words.

- They know how to dress, eat, and go to the toilet but may still need reminders.

- They struggle to read or write without step-by-step help.

- Socially, they might play next to others, but not with them.

- They may not fully understand danger, rules, or changes in routine.

Severe Intellectual Disability

Daily care becomes more hands-on.

- Speech is very limited some may not talk at all.

- They need help with almost everything: eating, bathing, dressing.

- Understanding is limited to basic, simple instructions.

- They may also have physical disabilities or medical needs.

- Many are very sensitive to noise, touch, or movement.

Profound Intellectual Disability

Full-time support is needed for life.

- These children may not walk or speak.

- They often have seizures, feeding difficulties, or serious health issues.

- They may respond to smiles, touch, or sound but very slowly.

- Daily care includes lifting, feeding, changing, and constant supervision.

- Most families work with a team of doctors, therapists, and caregivers.

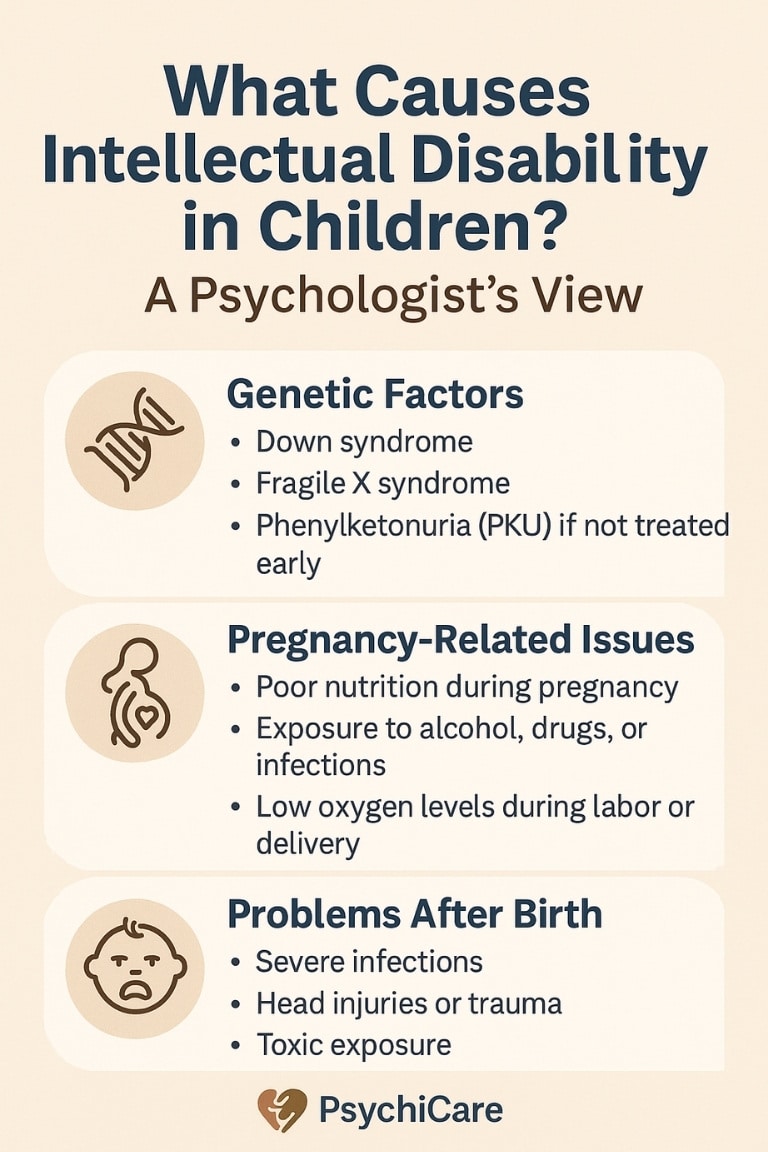

What Causes Intellectual Disability in Children? A Psychologist’s View

Parents usually come to us with fear and guilt.

“Did I miss something during pregnancy?”

“Was it the fever, the fall, the delayed speech?”

“Could I have prevented it?”

As child psychologist, I want you to know this first:

Intellectual disability is not caused by something you said or did out of love.

It’s usually the result of complex factors, most of which are beyond your control.

Here’s what we see most often in real-life cases:

Some Children Are Born With It (And That’s No One’s Fault)

Genetic conditions like Down syndrome or Fragile X are diagnosed early. But not all cases are obvious at birth.

Sometimes, a child appears typical and only begins to show delays around age 2 or 3.

These kids may have what we call global developmental delays, and only later are identified with a mild or moderate intellectual disability.

Brain Development Is Affected by What Happens Early

This includes:

- Lack of oxygen during birth (a difficult delivery, for example)

- Preterm birth many babies born before 34 weeks are at higher risk

- Severe jaundice that wasn’t treated in time

- Infections during pregnancy or infancy (like rubella, CMV, or meningitis)

None of these happen because you weren’t careful; they happen, and they’re hard. But with the right diagnosis and support, they don’t have to define your child’s whole future.

Nutrition and Stimulation Matter Especially in the Early Years

We’ve worked with kids whose brains were healthy but who were never spoken to, never played with, and rarely touched as babies.

Extreme neglect, poverty, or trauma can delay development.

And children who miss these early building blocks may later be diagnosed with an intellectual disability, even though it wasn’t genetic or medical.

But here’s the good news: these are often the children who make the biggest gains with love and structured therapy.

And Sometimes… There’s No Clear Cause

Not every child has a diagnosis like “autism” or “brain injury.”

Sometimes, we do the scans, ask the questions, and everything looks “normal” except the child is struggling.

In these cases, we focus less on “why” and more on what they need right now.

What We Tell Parents in Session:

- “No, you didn’t cause this.”

- “Yes, your child can learn.”

- “No, it’s not too late.”

- “Yes, you’re doing the right thing by asking.”

How Is Intellectual Disability Diagnosed in Children?

Diagnosis is often the hardest part not because the process is complicated, but because it’s emotionally heavy. Most parents come to us not looking for a label, but looking for answers.

They say things like:

“I just want to understand why they’re struggling.”

“Everyone keeps saying ‘wait and see’ but I’ve waited long enough.”

“She’s 6 and still can’t follow two instructions in a row. Is that normal?”

Here’s what the process looks like from a psychologist’s perspective:

It Starts With Your Observations

You know your child better than anyone.

If something feels “off” compared to other children, especially with language, memory, or how they handle day-to-day things, that’s reason enough to seek help.

We listen to parents closely. Many times, it’s a parent’s gut feeling that leads to the right diagnosis, not a school report or test score.

Developmental & Cognitive Assessments

We don’t rely on just one test.

Diagnosis involves looking at two big areas:

- Cognitive skills – how your child learns, reasons, and solves problems (this includes IQ testing, adapted for kids)

- Adaptive functioning – how your child handles real-life tasks like communication, social skills, and self-care

In other words:

It’s not just about “how smart” your child is it’s about how they function in everyday life.

What We Use in Practice:

- Developmental history: Milestones, speech, motor skills, play

- Standardised tests (like the WISC, Stanford-Binet, or Vineland)

- Behavioural checklists filled out by parents and teachers

- Observation during play or simple tasks is sometimes more revealing than any form

We Also Rule Out Other Conditions

Some children may seem to have an intellectual disability, but actually have:

- Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Learning disorders (like dyslexia or processing issues)

- ADHD or emotional trauma

That’s why an experienced psychologist will look at the full picture, not just scores.

When Is It Diagnosed?

While signs can show up in toddlers, formal diagnosis usually happens between ages 4 to 7 when school expectations make the differences more visible.

But we always encourage parents to come sooner.

Early diagnosis doesn’t label a child it frees them to get the help they deserve.

Some children may seem to have an intellectual disability, but actually have Autism Spectrum Disorder, Learning Disorders, or ADHD.

That’s why an experienced psychologist will look at the full picture, not just test scores. You can explore our full Child Assessments process for more clarity.

Is Intellectual Disability the Same as a Learning Disability?

Many parents use these terms interchangeably because schools, reports, or even doctors don’t always explain the difference clearly.

But here’s the truth, from a psychologist’s perspective:

They’re not the same. And confusing them can delay the right kind of support.

What’s a Learning Disability?

A learning disability means a child has trouble with a specific skill like reading (dyslexia), writing (dysgraphia), or math (dyscalculia) but their overall thinking and problem-solving skills are average or above average.

- These kids can be highly verbal, creative, or curious but they hit a wall with one subject.

- Their IQ is usually in the normal range.

- With special teaching strategies, many thrive in school.

What’s an Intellectual Disability?

An intellectual disability affects general learning ability not just one area.

- Children may struggle with basic concepts, instructions, daily routines, or self-care.

- They often have trouble with short-term memory, problem-solving, and adjusting to new situations.

- Their IQ is typically below average, and they need support across many parts of life.

How We Tell the Difference

During a full child assessment, we test both:

- Academic skills (to check for learning disorders)

- Cognitive functioning and adaptive skills (to check for intellectual disability)

A child can have both, and in fact, some children with mild intellectual disability also have ADHD or autism.

Can a Child Outgrow Intellectual Disability?

This is one of the most common and most painful questions we hear from parents:

“Will my child ever catch up?”

“Can this go away with therapy or time?”

Here’s what we want you to know, as psychologists who work with families every day:

Intellectual disability doesn’t go away, but children can still grow, improve, and thrive.

What That Really Means

Intellectual disability is a lifelong condition. It’s based on how a child’s brain develops and how they process learning, memory, and everyday problem-solving.

That said, how a child functions can improve greatly with:

- Early therapy

- Consistent support at home and school

- A learning environment that matches their pace and strengths

Some children with mild intellectual disability may grow into adults who work, build relationships, and live independently with or without support.

Progress Looks Different for Every Child

We’ve seen children who:

- Didn’t speak until age 6 but now express themselves beautifully

- Couldn’t tie their shoes at 9 but now travel to school on their own

- Struggled in early primary years but slowly learned to read and write with pride

No, the diagnosis doesn’t vanish.

But the child inside it still grows with the right structure, love, and belief in their potential.

The real question isn’t “Can they outgrow it?”

It’s “What can they still grow into with your support?”

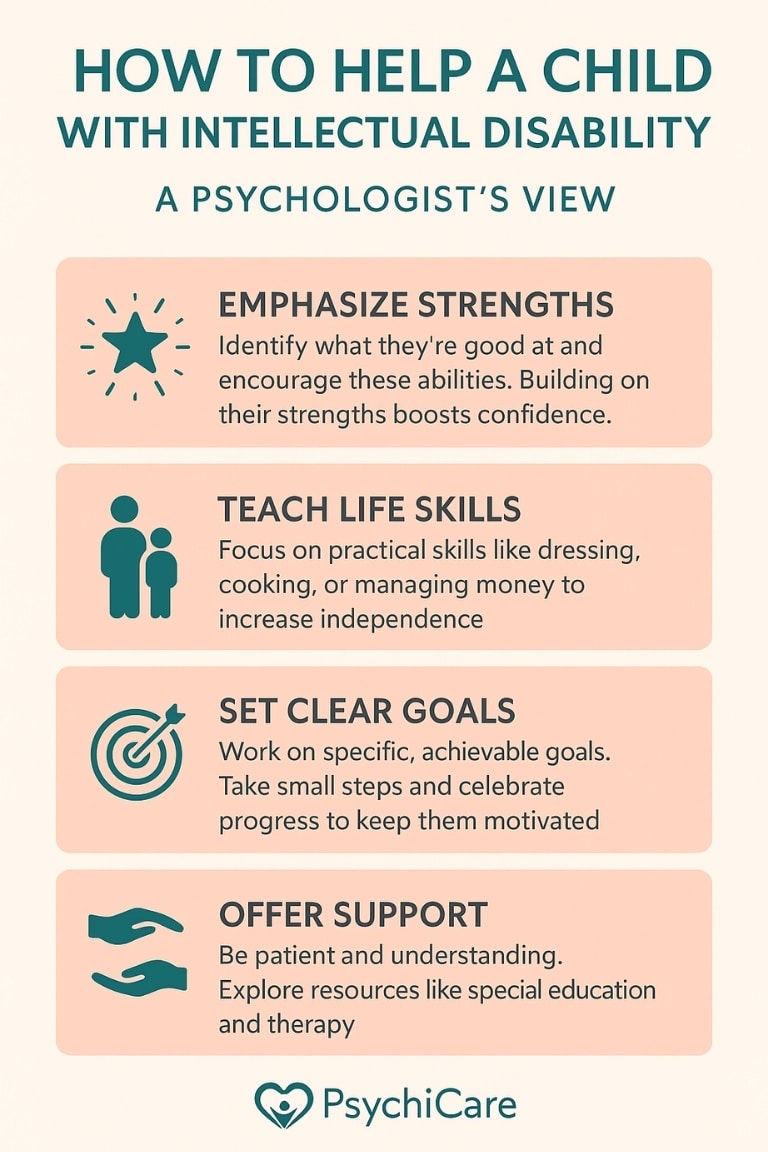

How to Help a Child With Intellectual Disability: A Psychologist’s View

In therapy, this is one of the most honest questions we get from parents:

“I know my child is different. But what do I actually do every day to help them?”

They’ve already Googled “how to support a child with special needs.”

They’ve already been told to “be patient,” “stick to routines,” and “give praise.”

And still they feel stuck, lost, and alone.

Here’s what we actually tell families in sessions, based on real work with real children:

1. Stop Trying to Close the Gap. Start Building From Where They Are

One of the biggest mistakes we see is this:

Parents are working so hard to “catch their child up”… they miss who the child is right now.

Instead of comparing to what other kids can do, start by asking:

- “What can my child do independently today?”

- “What is still hard?”

- “What does my child avoid not because they’re lazy, but because it overwhelms them?”

2. Assume They Want to Learn Even When They Push You Away

Kids with intellectual disabilities often:

- Avoid tasks that make them feel stupid

- Shut down when asked too many questions

- Melt down when they feel lost or embarrassed

We’ve worked with children who didn’t speak at school for a year until someone taught them through drawings.

We’ve seen kids freeze during math until we removed the timer.

These kids want to learn. They just can’t do it the way everyone else expects them to.

3. Watch for Non-Verbal Wins

Don’t wait for big milestones. Look for signs your child is making mental shifts:

- They pause before needing your help

- They point, instead of dragging your hand

- They sit a little longer during a difficult task

- They repeat a word you didn’t think they heard

4. Make the Environment Do Half the Work

Children with intellectual disabilities rely heavily on external structure.

The more the environment is clear and repeatable, the less pressure they feel to “figure things out.”

This means:

- Same space, same tools, same order of steps

- Fewer choices = less confusion

- Visual supports (picture steps, colored drawers, timers) = more independence

- Less talking, more showing

5. Therapy Shouldn’t Be About “Fixing” It Should Be About Translating

When we work with a child who has an intellectual disability, our job is not to “fix” them.

It’s to figure out how their brain works, what overwhelms them, and how to translate the world into something they can actually use.

Sometimes that means:

- Using rhythm and music instead of spoken instructions

- Turning routines into step-based games

- Allowing silence before expecting a response

- Accepting hand gestures instead of words at least for now

What I Tell Every Parent:

“Your child may not learn the way other kids do.

But if we find the way they learn… they can go further than anyone thought.”

FAQs About Intellectual Disability in Children

How do I know if my child has an intellectual disability?

You can tell if your child has an intellectual disability if they are learning much more slowly than other kids their age. They may struggle with speaking, understanding instructions, solving problems, or doing daily tasks like brushing teeth or getting dressed.

What are early signs of intellectual disability in toddlers?

Early signs of intellectual disability in toddlers include delayed speech, not responding to simple commands, not pointing or playing pretend, and needing more help than expected for their age.

Is intellectual disability the same as a learning disability?

Intellectual disability is not the same as a learning disability. Learning disabilities affect only specific skills like reading or math, while intellectual disability affects overall thinking, learning, and daily functioning.

Can a child outgrow intellectual disability?

A child cannot outgrow intellectual disability, but they can improve a lot with early support, therapy, and a structured learning environment.

What causes intellectual disability in children?

Causes of intellectual disability in children include genetic conditions, birth complications, brain injuries, infections, malnutrition, or extreme neglect. In some cases, no clear cause is found.

Can a child with intellectual disability go to regular school?

Children with intellectual disability can go to regular school if they have mild to moderate needs. Many benefit from extra support, smaller classrooms, or special education programs.

Is speech delay a sign of intellectual disability?

Speech delay can be a sign of intellectual disability if it’s combined with problems in understanding, social skills, or everyday learning. Some speech-delayed children do not have intellectual disability.

How is intellectual disability diagnosed in children?

Intellectual disability in children is diagnosed through developmental and psychological assessments that test thinking, problem-solving, and daily life skills. It includes IQ testing and reports from parents or teachers.

Can a child with intellectual disability live a normal life?

Children with mild intellectual disability can live a mostly normal life, especially with early support. Many learn to manage daily routines, attend school, work, and live with some level of independence.

How can I help a child with intellectual disability at home?

You can help a child with intellectual disability at home by using simple routines, breaking tasks into steps, repeating instructions gently, and celebrating small wins. Visuals, structure, and consistent praise are very effective.